All we can hear is the howling of the storm

Dec 05, 2025 1:02 am

The artist Marek Zulawski, translation & Polish-British culture

Hi,

This week, with the days getting colder, I thought I'd translate something my father wrote about sailing, a sport you can't really do much of at this time of year unless you've got a bit of a masochist streak in you. And this story definitely won't make you want to go sailing either. It's from 1937, not that long after my father first moved to London.

---

“Give him some rum!” I shout to the skipper, but the wind snatches the words from my mouth.

'Mediterranean Cruise' by Marek Zulawski, 1975

It's the year 1937. Anthony, Alistair and Maurice are taking me by car to Whitstable.

There, an old skipper is bustling about on the deck of a large river barge that's been converted into a yacht. All three of them are playing the part of old sea dogs: sou'westers, windbreakers, sweaters up to their chins. Only the skipper's wearing a plain old jacket and tie. His flat cap sits on his head without flair, simply practical.

We're sailing. The barge's hull is shallow in the water and its centre of gravity is too high. Its large reddish sails, appropriate for a river barge, carry us well on a light side wind but not at all upwind. Having some sailing experience, I say that on the sea, due to the waves, centreboards are useless. There's no keel. The others don't care, although the skipper nods at me knowingly.

We play cards. I make drawings.

We glide smoothly over to Dover. We meet some girls. Gladys and Margot — giggling on the sand. But we sportsmen, we don’t have time to dilly dally further. There's the call of the sea. The barge's owner, Anthony, has suddenly decided to sail to France, even though it's already well past noon. So off we go.

The weather, beautiful at first, changes rapidly.

“The barometer’s dropping like a rock,” says Alistair suddenly, laughing foolishly, as if it's of no concern to him. We can't see land anymore, but a black cloud appears just above the horizon, growing with unusual speed.

“A storm's coming,” says the skipper, pulling on a yellow oilskin suit.

Moments later, half the sky goes dark, and a white line of foam appears on the horizon.

“Reef the sails!” orders Anthony. But on a river barge like this, that’s not so simple — unlike on a modern yacht where it’s a snap. Before we manage to furl the big sail, the wind hits. The fact that no one was swept overboard is a miracle to me. Because that whole huge reddish sail, only half reefed, went overboard with the mast. The second sail filled up with wind like a balloon before bursting with a loud crack along the batten.

We let the elements carry us. We have no motor, we can't do anything else.

The wind is so strong it’s hard to communicate even when shouting in each other’s ears. All we can hear is the howling of the storm. Waves crash against us from behind and we can see them overtaking us. We drift helplessly, like Noah’s Ark on the third day of the flood.

And suddenly, as if cut with a knife, the howling stops. The wind disappears. Huge dragon-like waves rise up vertically around us and crash down on the deck, flooding everything. It's the eye of the cyclone.

But the ominous silence only lasts a few minutes. The storm-tossed sea is struck again, this time by wind from the opposite direction. Now it's shoving us toward the coast of France.

At 1 in the morning, we see lights. At 2am, we crash full-speed into the concrete breakwater of the port of Calais. I was at the helm and managed to partially soften the impact by turning the barge sideways toward the wall where fenders and car tires were already hanging in preparation. But once we lost all speed, my presence at the wheel became pointless.

So I get up and try to assess the situation. The sea is bashing us against the concrete. The waves lift the barge up, smashing the fenders and the hull, then push us back and down — only to slam us against the concrete again, lift us up and then throw us down. Again and again. Splinters and fender pieces fly through the air. Steel cables and ropes whip around like snakes on the flooded deck. The lifeboat's floating upside down in the sea...

If it keeps going like this — I think to myself, oddly calmly, which surprises even me — if it keeps going like this, the whole barge will be torn to pieces. The deck is groaning infernally — below deck, a vomit-covered Maurice lies among broken eggs and smashed porcelain, covered in sugar, flour and pasta.

I pull him out into the fresh air, which revives him. He’s the only one of us who speaks fluent French. I come up with a plan: we’ll throw him onto the breakwater when the barge rises, then he can summon a French tugboat. Someone has to pull us away from the wall before we're completely smashed to bits.

I stand and look. Between the hull and the breakwater, the water looks like it's boiling. Foam is spraying in every direction. When the barge is low, the rocks are exposed. When it's high, just for a moment, it's almost level with the breakwater.

“Let’s throw him onto the breakwater!” I yell into Anthony’s ear. Anthony agrees. He nods his head.

“Good idea, Maurice will call for help.” But Maurice is white as chalk, his teeth chattering with fear.

“Give him some rum!” I shout to the skipper, but the wind snatches the words from my mouth.

“Brandy, une petite goutte de cognac,” whimpers Maurice, praying loudly in French.

Moments later, grabbed by four pairs of strong hands, he’s flung into the air, much too high, and lands face-first on the breakwater. But he raises his hands in a joyful gesture of salvation, and runs toward the port in a stagger. A moment later, he disappears from sight.

I sit back at the now-useless helm and think. Maybe the breakwater doesn’t connect to the shore, and Maurice won’t bring help until dawn. He didn’t even have a flashlight. But will the barge hold out until morning, and can we hold out these horrible impacts against the concrete, while each one turns our guts inside out?

If not, we’ll have to jump.

I look again — as objectively as possible — at the churning space between the hull and the wall and tense all my muscles in a test. Yes, I could probably make it, but it would have to be one hell of a leap... If I slip, the next hit would crush me against the wall — that's if the waves didn’t break my bones against the concrete first.

And then suddenly — from very far away — a searchlight appears.

Moments later, a huge tugboat, black as a bull, emerges from the early dawn and approaches us. We’re saved!

They shout to us through a loudspeaker in French to grab their rope. Anthony leaps up first — it is his barge smashing against the wall, after all — but he grabs it wrong and drops it. Alistair catches the next one, runs with it — and slips and falls hard on the wet deck. The skipper has a broken leg — probably fractured — so he can’t take part in our game of catch.

So Anthony tries again. He gets a good grip but has to let go at the bow because he runs out of deck. The French are shouting and gesturing at something — no one knows what.

Then my turn comes, and a sudden realisation hits me. I understand what's happening. Both of my friends had grabbed the rope mid-deck. As a result, by the time they tried to tie it down, they were already at the bow. No more deck so they had to let go.

So I stand right on the stern and can already see the French clapping. That's apparently what they wanted. The tug approaches us cautiously and then pulls away again, fearing a collision. Now I see it making an arc to pass us from the stern. The rope — perfectly thrown — falls almost right into my hand. I grab it and run with it the entire length of the deck. The tug glides slowly in the same direction. I have a good grip, and though some of the line slips from my hand, I throw myself down on the bow deck and tie the line to the capstan. Only later do I mentally note the fact that it's red with my blood.

And suddenly a miracle occurs. The pounding against the wall stops — we're sailing, clearly sailing into the port. The deck calms down — the rolling subsides, the roar of the breakers crashing against the breakwater falls silent. We enter the calm waters of the inner harbour. There along the quay, we see Maurice jumping for joy with some guy in a captain's cap. They jabber in French and slap each other's shoulders. We're saved.

What followed afterward is shrouded for me in the mists of time — and alcohol. The British consul in Calais threw a splendid party in our honour. We went to some bars afterward and visited some people. In the yacht club, we gave interviews to the press, which thanks to Maurice's French appeared in the local paper. We posed for photos as heroes — each individually and all together — against the background of our wreck's broken masts.

And the next evening, the Norwegian consul, who had probably envied the British consul's social success, staged an excellent piss-up with us in the starring roles. It ended in a certain house with a red lantern over the gate.

It was on that memorable night — drunk and exhausted to the last limits — that I found myself alone in that square and encountered that monument. Naturally, I knew it from reproductions, but I hadn't remembered it stood in Calais. "Rodin, Rodin," I repeated — and something strange happened in my throat. A spasm passed through my heart, and my eyes filled with tears. From drunken fatigue and emotion, I sank to my knees. The townsfolk of Calais raised their hands and looked at me. I wanted to be one of them, but my strength failed me. Curled up under that monument, I fell asleep and spent the rest of the night there. I was 28 then.

We returned to London separately, picked up by various yachtsmen. I ended up on a splendid motor yacht, where in a luxurious cabin a black-as-ebony negro in red livery served whisky and soda. They took me up the Thames, all the way to Westminster itself...

'The Burghers of Calais' by Auguste Rodin, via Wikipedia

If you'd like to read another story about the high seas from my father's autobiography, there's one here: How to swear like a sailor, 1928

---

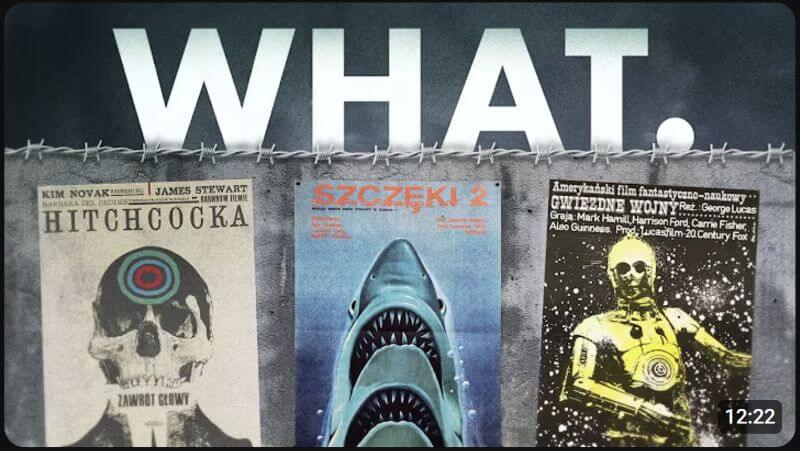

Polish movie posters are confusing

If you're unfamiliar with the weird world of communist-era Polish movie posters, then prepare yourself to be delighted. Here's a little video explaining how US film posters were ditched for new avantgarde creations and how it became a bit of a tradition.

---

That's all for this week. Many thanks for reading. If you want to support the newsletter, please forward it to a friend or donate here.

Adam

Adam Zulawski

TranslatingMarek.com / TranslatePolishMemoirs.com / Other stuff

👉 Help fund the translation of Studium do autoportretu via Paypal 👈

Sent this by someone else?