I burned my tongue on the tea

Jul 31, 2025 10:16 pm

The artist Marek Zulawski, translation & Polish-British culture

Hi,

This week, I've translated the story of how my father came to start working on a series of paintings all about Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh is the first heroic story in recorded history, and the basis of lots of other famous legends and tales.

The strange thing is that it's only in the last few decades that Gilgamesh has been available to read properly - the original is on clay tablets scattered around the world's museums, and new parts of the epic are still being discovered.

---

Can you borrow that book out for me?

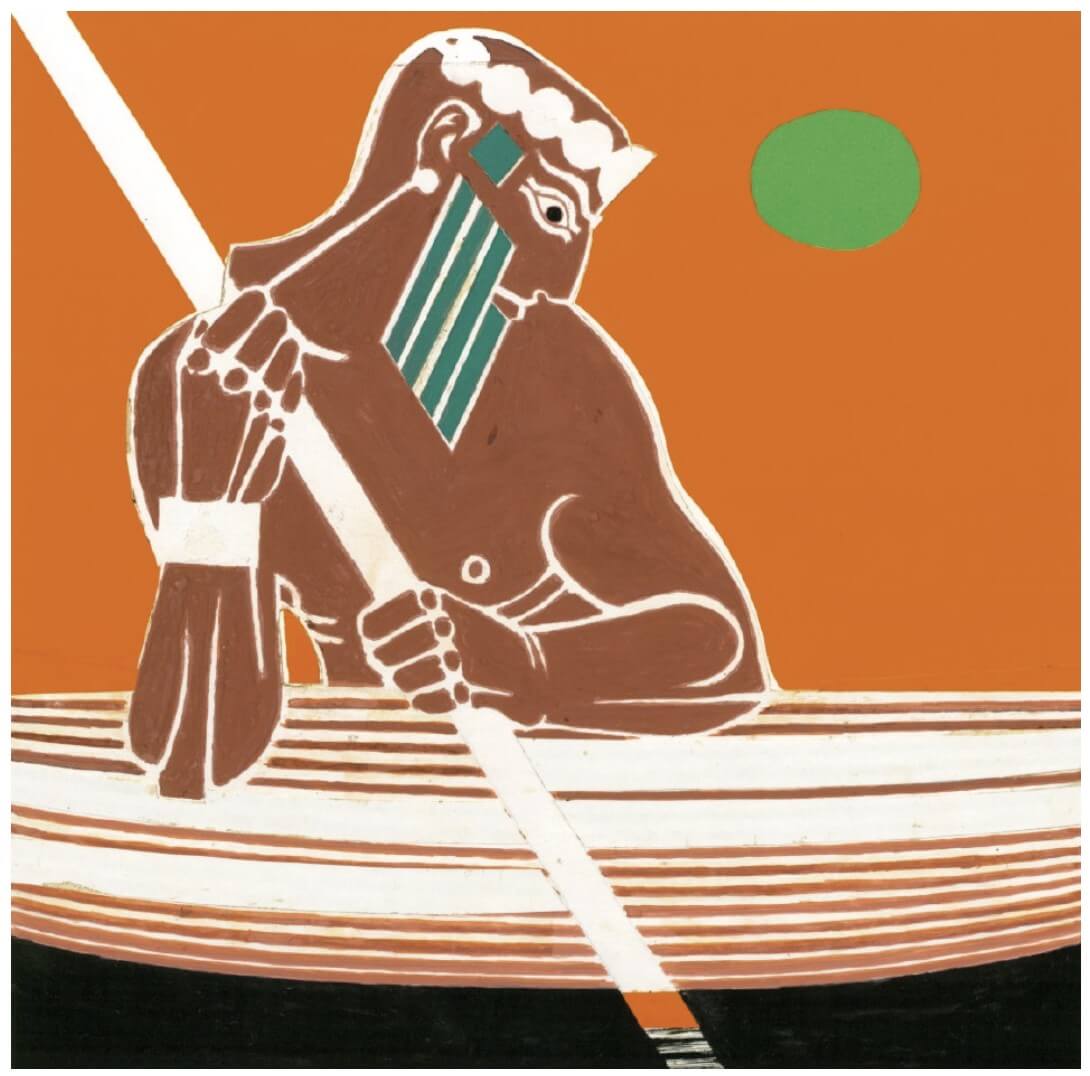

'Gilgamesh on the Waters of Death' by Marek Zulawski, from the Gilgamesh series

In June 1980, after an exhibition of my paintings in Warsaw, I learned that the State Publishing Institute was planning on launching an ambitious series titled Bibliotheca Mundi, which would apparently include monumental works of literature from all eras, cultures and civilisations. Early Hindu and Chinese manuscripts, Homer, the Old Testament, the Quran, the Talmud and so on.

A library like that seems unthinkable without Gilgamesh, the earliest epic in the world.

So I start talking about it — or rather, thinking out loud — that if there were a good translation, one could produce a Polish edition of Gilgamesh with my serigraphs. Because — I said — there had been a beautiful translation by Józef Wittlin, which I still remembered from my early youth. I must’ve been a teenager when I read it in Zakopane, where 'Józio' — as we called Wittlin — often visited us from Lwów [Lviv today]. He’d sunbathe in a deck chair in our garden, greased up with lard… We all loved him dearly. He was sad, cheerful and full of uncertainty. He sighed a lot and often asked our mother for advice…

Half a century later in 1967, he invited me to lunch in New York — which, as I saw with my own eyes, was paid for not by him but by Menkes. When I brought up his Gilgamesh, he lamented that not a single copy existed anywhere in the world. He’d inquired, searched, written to Warsaw — all in vain. He didn’t have one himself either.

Well… when I was telling all this to Magda and Hania, Magda serenely poured us some tea before saying, “I saw Gilgamesh in the university library yesterday, but I don’t know whose translation it was.”

I burned my tongue on the tea. I started shouting in frustration.

“For God’s sake, girl. Check as soon as possible: the author, the year, the publisher — everything you can!”

She checked the next day. Yes — it was Wittlin’s, published in 1922 in Lwów, based on the German transcription by Professor Burckhardt.

“Wonderful. Can you borrow that book out for me?”

“They won’t lend it out. They say it’s the only copy in the world. What am I supposed to do?!”

“Ask if they’ll let you copy it!”

“They won’t allow that either.”

“So, what now?”

Magda arranged, at an odd hour, for a university friend to come and photograph the entire book, page by page.

So I go to the State Publishing Institute for a meeting with Skórnicki, the editor, carrying slides of my serigraphs in one pocket and photographic prints of Wittlin’s Gilgamesh in the other. I tell Skórnicki that a new edition of the epic is about to be published in London — probably in both English and Arabic — using my illustrations, and that I thought perhaps the institute might be interested in a Polish version using Wittlin’s text.

“Yes, yes, of course,” replies Skórnicki, “but the problem is that we don’t have the text…”

Only then do I pull out the prints, like a magician pulling a white rabbit out of a top hat. He was speechless.

“Where did you get this?” he gasped. “It’s impossible — we searched everywhere, we even asked Wittlin’s widow!”

I calmly explained the whole detective-style caper and showed him the slides of the illustrations.

“As for the illustrations, I don't need a second opinion,” said Skórnicki. “We know your work — I attended your exhibition… It’s just a matter of the text, which none of us here have read. We’ll read it once we've made some larger prints and get back to you in mid-July…”

And that’s where things stood.

'Shamhat Waits for Enkidu' by Marek Zulawski, from the Gilgmesh series

It would take another six years before the new Polish version of Gilgamesh including my father's paintings was published - a year after he died. Today, the Gilgamesh series of paintings are on permanent display somewhere in Kraków, if I remember correctly.

If you'd like to know more about the search for the missing fragments of the Gilgamesh story, and how AI is helping (yes, even archaeologists need to worry about AI taking their jobs 😅), check out this fascinating article.

---

Using Polish with an English brain

Well, Scottish technically. This entertaining article by Andy Hall, a Scot living in Poland, talks about trying to get used to Polish syntax while thinking in English.

For example, he points out the lack of 'May I?' in Polish means he keeps using 'Can I?' - and literal-minded Polish shop attendants keep wondering why he's asking them if he's capable of doing things.

---

That's all for this week. Many thanks for reading. If you want to support the newsletter, please forward it to a friend or donate here.

Adam

Adam Zulawski

TranslatingMarek.com / TranslatePolishMemoirs.com / Other stuff

👉 Help fund the translation of Studium do autoportretu via Paypal 👈

Sent this by someone else?