The closest thing we have to eternity

Nov 06, 2025 7:47 pm

The artist Marek Zulawski, translation & Polish-British culture

Hi,

Recently, I'd been thinking about planning a trip to Egypt in the near future. I thought I'd randomly check my father's autobiography for mention of the country, and, lo and behold, I found something entertaining to translate for the latest edition of the newsletter.

---

Only in the desert can you understand how terrible a thing the sun is

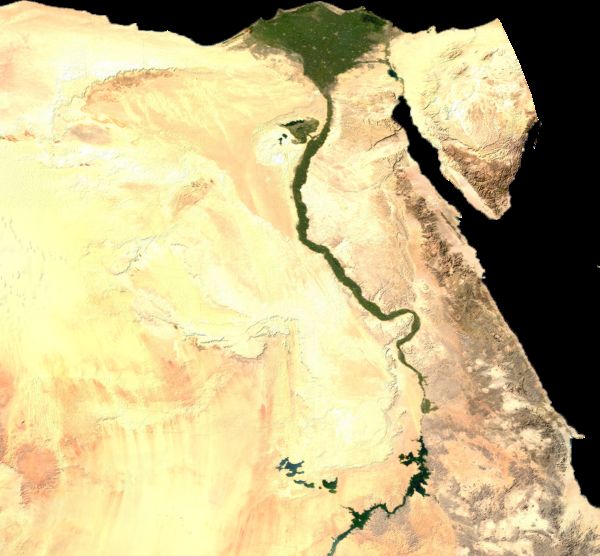

A satellite photo of Egypt, via Wikipedia

I flew to Cairo in October 1972. Egypt, in reality, does not exist. From the air, you just see a narrow little strip of green on both sides of a mighty river that flows for thousands of miles without tributaries. It's squeezed between two endless deserts: the Libyan to the west and the Eastern Desert to the east. In some places, the deserts almost touch each other.

But there are works here. Extraordinary, superhuman, inconceivable — impossible, it seems, to have been carried out at all.

"Is this all authentic?" loudly asks some American woman in Cairo's richly-stocked Egyptian Museum. "Yes, madam," replies the guide, who has the face of a Bedouin. "Everything here is authentic except me."

Indeed, this unfortunate Arab-Albanian mixture that populates the country is not Egyptian — they are not descendants of the builders of the great temples, sarcophagi, sphinxes, colossi and pyramids.

The pyramids in Giza are the closest thing we have to eternity. In a noisy suburb of Cairo, they stand in their own sphere of silence. Nothing is capable of disturbing it.

In Aswan, it’s 50°C. The desert breathes a terrible heat, much like a blast furnace. The few passers-by, blackened and thin as sticks — dried up — hide in the shade of every wall, fence, palm, donkey… Deadness.

Luxor greets us with an evening stench and herds of the unemployed camping on the streets. Whole families live in holes dug into the banks of the Nile, roofed with palm leaves. Flocks of hungry children in tattered burnouses and shirts run after each tourist. If you give them a few coins, they'll never leave you alone. Underage boys and girls perform some sort of pantomime before you, tempting and offering their services. They run off, then return again.

At the hotel, on its absurdly Swiss veranda, there's the constant commotion of group tours. Suitcases are brought in and out — people stand and sit — you hear every language in the world. An unbearable din.

But at night, there's only cicadas. In the absolute darkness, stumbling on the unfamiliar bank of the huge river, I kiss the red-haired and slender Angela. We search in vain for a place to lie down, but at every step we bump into white burnouses slipping by on every side. In the morning, I realise the supposed rough ground was a rickety boulevard running along the street.

That night, I kept the fan off so that it didn't drown out the footsteps. I kept waking up and, ignoring the insects, opened the door to the garden. The air was hot from the day and smelled sharply like geraniums in cold frames. A wooden porch ran around the garden. I closed the door and went back to bed. The porch creaked. I jumped up again.

At dawn, I startled a peculiar bird with a flame-like crest that, with a hellish scream, flew in a crooked arc to the opposite room’s door where Angela was staying with her toad-like mother (who did not hide her hatred for me). Was it a hoopoe or some other devil?

The Valley of the Kings is as dry as a skull. Not a drop of water, not a blade of grass. Blinding heat under a blue sky. The colourful scuttle of tourist groups crawls in and out of the eye-socket-like tombs hewn into the rock. The silence of millennia, desecrated. Or perhaps just one era, completely and irretrievably filled. All the graves are empty.

The tomb of Ramesses II: hall after hall carved into sheer rock. The walls are completely covered with symbols cut into plaster — hundreds, thousands of tiny sections precisely filled with stories of events and rituals. Ceilings painted with zodiacs and sacrificial animals. All this could only have been made possible by an army of craftsman-labourers under the direction of hundreds of artists and a genius architect.

The question arises: where did all these masses of people live — how did they have enough food and water in that terrifying rocky desert? And besides, how could a narrow strip of land called Egypt have so many skilled artists? And who was farming while those people — cut off from the world and presumably guarded by armed supervisors to keep them from escaping to their families — spent their lives in the inaccessible Valley of the Kings? Because this much work on a single pharaoh’s tomb must have lasted decades. How was this all organised without electricity, water, refrigerators or preserves? It seems impossible. Evidently, they must have possessed some unknown technical means that surpassed everything the orthodox version of history today wants us to believe about transport and supply methods in ancient Egypt.

And how did they place the superhuman-sized columns of Karnak so close together?

Karnak Temple, 2022, via Wikipedia

But there are even stranger things. Catacombs cut into rock with side chambers that fit inside them colossal granite sarcophagi for sacred bulls. How did they bring them in and arrange them with such incredible precision in rooms that they nearly completely fill? Not to mention, this granite is not native to the area and must have been brought from afar by some mysterious means of locomotion. And considering their great weight, how could these massive sarcophagi have been put into such a tight space? There’s no room to turn around, let alone build powerful tripods or suspend blocks needing high ceilings or fit in the large number of people needed to operate everything. In my opinion, this could only have been done by removing the weight from the granite sarcophagi. The builders of the pyramids must have known how to counteract gravity as well as how to cut stone with some kind of laser.

In front of the temple at Luxor is an avenue of granite sphinxes. They may not be that colossal, but there are hundreds in two rows — and almost all of them are identical. But even if they weren’t, how many sculptors — I ask you — would have to have been engaged in chiselling, and for how many decades, since they only used chisels and hammers? And what sort of excellent tempered steel would they have needed to chisel granite? Yet somehow, these sculptures appeared in the Bronze Age.

The borders of the desert blur together. Suddenly one steps out of the coach into such dazzlingly bright sand that you have to shield your eyes. All the colour is devoured by light.

Sometimes, at the top of huge sand dunes, very far away in the heat-shimmering air, you see a small plume of dust. The plume disappears among the dry waves of the desert and reappears closer, a bit larger, until finally, you see it’s an Arab on horseback crossing this inhuman land at a gallop, racing to reach a town ready to welcome him with shade.

Only in the desert can you understand how terrible a thing the sun is. Relentless, unyielding, destructive — indifferent.

I asked a Bedouin whether he liked London, where, he said, he had once been on a trip. "Oh yes," he replied with genuine enthusiasm. "So much rain, so much water..." For an Arab, the symbol of life is water, not the sun as it is for us.

The shores of Lebanon are green. This is where the Crusaders landed. Their gigantic castles still crown its wooded hills. But then, just beyond the Anti-Lebanon Mountains and the Mount of Transfiguration, stretches the Syrian Desert.

In Beirut, an obscenely rich place, there are plenty of fat sheikhs and Rolls-Royces. On the promenade, slender youths approach asking for your hotel room number. The ladies seem horny. While drinking aperitifs on a café terrace, as if we were in Paris, Angela draws her chair next to mine and presses her whole body against me. We feel the hot night air and the mighty roar of waves crashing somewhere on the rocks below... At the hotel, I'm greeted by the unfriendly stare of the mother-toad, who's been waiting impatiently in the lobby for her daughter's return...

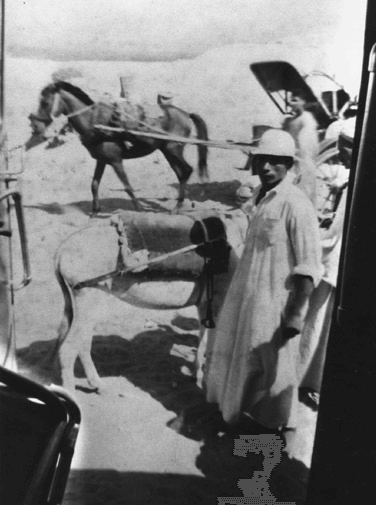

A photo from Marek's trip, 1972

My father says, quite rudely, that Egyptians are an Arab-Albanian mixture, which is pretty off, even at the time he wrote it I'm sure. Interestingly, there have been a lot of DNA studies of Egyptians over the past couple of decades. They do have a mix of influences in their genes, but analysis has resolutely shown they are not Arabs, and no study mentions any link with Albania.

As to my father's incredulity about how all of ancient Egypt's wonders could have been built, I'm guessing he might have been convinced by that popular conspiracy theory that the real builders were aliens. Not too much DNA analysis on that one, mind you.

---

Ultimate new restoration of 'Possession' coming out

My late cousin Andrzej Żuławski's most infamous film Possession was deemed a 'video nasty' in the 1980s, and was definitely mostly watched on dodgy VHS for many years. But now there is a luxuriously packed new edition in full 4K (which I understand is like the HD of HD).

It's out on December 8th, so just in time for Christmas - perfect for the more warped loved ones in your life.

---

That's all for this week. Many thanks for reading. If you want to support the newsletter, please forward it to a friend or donate here.

Adam

Adam Zulawski

TranslatingMarek.com / TranslatePolishMemoirs.com / Other stuff

👉 Help fund the translation of Studium do autoportretu via Paypal 👈

Sent this by someone else?