VC Fund Economics: Swing For the Fences

Mar 14, 2021 8:34 pm

👋

Hello ,

The other day, I was chatting with a group of folks who were interested to start a fund to invest in young startups. We talked about the structure of a fund, sources of capital, the economics and portfolio construction. When we discussed portfolio construction and the subsequent performance of a fund, it dawned upon us that there’s some similarities between Venture (VC) funds and baseball.

Most of the time in a baseball game, there will be lots of hitters, while the batters strive to hit home runs. Those hitters do count, yet the home runs are what makes the difference.

A VC portfolio is not so much different. The portfolio’s performance usually follows the ⅓, ⅓, ⅓ hit rate rule of thumb. The first third represents portfolio companies that don't work out hence returning zero money. The following third will become ‘zombie’ companies. These zombies are not quite failures, yet they are not returning high returns. Perhaps breakeven, if you’re lucky. The final third are the startups that will become successful and provide spectacular returns (and wealth) to the fund manager, i.e. General Partners (GP) and their investors, or Limited Partners (LPs).

Swing big or miss big, just like Babe Ruth (one of baseball's greatest players).

“How to hit home runs: I swing as hard as I can, and I try to swing right through the ball… The harder you grip the bat, the more you can swing it through the ball, and the farther the ball will go. I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big.”

Source: Pinterest

Monkey Business

There’s research that says a monkey throwing darts on stock pages might provide financial returns as good as or better than an active investor in the public markets. Judging by the ⅓, ⅓, ⅓ rule of thumb, perhaps the LPs might as well hand their money off to a monkey instead of a fund manager?

Source: Twitter

I don’t know enough about hedge funds/public market investments, yet there are a bit more nuances when it comes to VC (and other private market) investments. Unlike public markets with real-time share prices, quarterly earnings and research analysts, there isn’t a lot of information available to outsiders when you want to invest in privately held startups.

Can This Startup Return the Fund (And More)?

In a typical scenario, out of 100 potential startups to invest, a VC fund might cull the list down to 10 of them for further evaluation. From the 10, only 1 or 2 startups might make the final cut. The decision to invest in these 2 startups may rest on the size of the addressable market, team background and capabilities, and whether the products or services offered solves a problem that is differentiated from other competitors.

And there is one fundamental criteria that might not be widely known, is this qualitative yardstick - can this startup return the fund i.e. break even (and some more)?

Even the founders discussing potential investments with a VC might not be aware of this question.

Yet the answer to this question more often than not will determine the investability of the startup, which might influence the fund’s performance and reputation.

Let’s revisit Kembara Ventures (Kembara) from the last post (link to older post) to illustrate this scenario.

Fund size: $100mn

Fee: $2mn or $20mn over 10 years

Remaining capital available for investments: $80mn

Average check size per investment: ~$5.3mn

Total number of startups under portfolio: 15 companies

Under these parameters, Kembara invests $5.3mn in XYZ.com, in return for 20% ownership in the company. After 8 years, XYZ became the largest NFT marketplace and went public on Nasdaq. The IPO was successful and XYZ’s market cap reached unicorn status at $1bn.

At IPO, Kembara still owns 20% of the company and the stake is now worth $200mn ($1bn x 20%). It is a 25x multiple on the initial investment ($200m / $5.3mn).

The $200mn return from that one investment is more than the original fund size of $100mn. In this case, Kembara will distribute the first $100mn to the LPs, and then split the remaining $100mn profit on a 80:20 ratio. The LPs get $80mn, while Kembara takes home the remaining $20mn.

This is what we call when one deal “returns the entire fund.”

Do you recall the ⅓, ⅓, ⅓ hit rate rule? For a portfolio of 15 companies, where ⅓ or 5 of them have the potential to become winners, there could be another one or more companies that might return the fund.

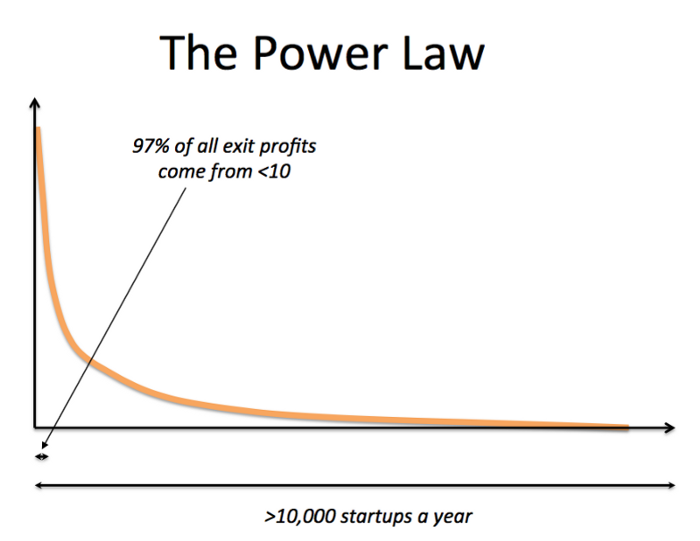

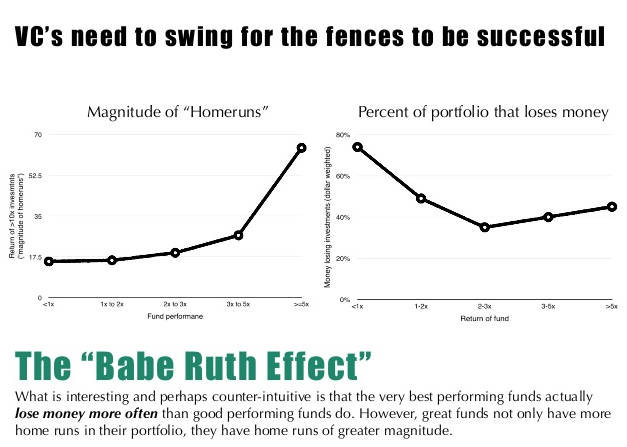

One common saying in VC is that ‘lemons ripen early’. It means, bad investments in a VC fund usually manifest themselves soon after the initial investments. The winners on the other hand, take longer to mature and when they do, they can provide phenomenal outcomes to the investors. In other words, the returns in the venture industry follows the Power Law distribution, i.e. a small number of investments will yield the greatest outcome.

Source: Noteworthy, The Journal Blog

Some of the great VC funds recently had (or going to experience) one or more of their investments paid off so huge that it will make more than one fund.

A case in point. Garry Tan’s Initialized Capital was among the first seed investors in Coinbase by writing a $150,000 check in 2013, out of its first fund, the $7mn Initialized Capital Fund I 2012 vintage. Assuming that the fund top ups in stake over Coinbase' subsequent fundraising rounds, the total investment could total $1mn with an estimated ownership of 0.5%. At the expected Coinbase's direct listing market cap of $100bn, this might translates into a $500mn windfall or 500x multiple (499,000% gain) on its seed investment and definitely returned the $7mn first fund it raised in 2012. And some more...it could also return Initialized Capital subsequent funds with this one exit.

Similarly, Union Square Ventures led the Series A investment into Coinbase in 2013. I imagined the fund also exercised its pro-rata rights and invested in Coinbase’s subsequent fundraising rounds to maintain its ownership, which I assumed came out to $10mn over the years. According to Coinbase’s S-1 filing, USV owns about 7.3% of the company. This means that USV stands to gain $7.3bn out of $100bn estimated valuation.

The investment in Coinbase is expected to return a whopping 730x multiple (729,000% gain) on its initial $10mn check size. The investment was made on its 2012 vintage fund with a size of $200mn. The $7.3bn gain will definitely return the USV 2012 fund (and more!).

Swing Big or Go Home

It is not easy to internalize the venture capital business model. In the early years of a VC fund (the first 4-5 years typically), there are only cash outflows, without any visibility in the near term of money coming in.

Source: Chris Dixon, A16Z

Investment returns for VC follows a power law rule. A small subset of investment according to the ⅓, ⅓, ⅓ rule of thumb will greatly influence the performance of any particular fund.

Venture investing does look like a tough business model. It requires the GPs to raise substantial funds at the outset. Scour for investable startups and make an educated guess as to which company might be successful in the future. The GPs exemplify the Babe Ruth effect: they will swing hard (make lots of investment), and in the process they may experience lots of losses in their search for startups that can return the fund, or in other word hit the home runs.

Stay cheerful,

Reez Nordin

If you like what you read, do share this link with folks in your network for them to sign up at

https://sendfox.com/spicyvc