P D Ball’s Newsletter No.16. A little about chariots!

Jul 29, 2025 9:26 pm

P D Ball’s Newsletter No. 16

Hello! I hope you’re doing well!

Contents:

- First words

- Brief history of chariots and why Alexander the Great easily beat them

- Summer Specials: free books!

First Words:

I hope you’re doing well and enjoying the summer! I’ve been very busy and have lots to report on. First, the audiobook for They Call Me Princess Cayce is finished. It’s narrated by the amazing Briony Rose Smith. If you live in the USA or UK, and are an Audible user, then I have a limited number of codes that will get you the book for free. Please send me an email at pdballwrites@gmail.com and if there are codes remaining, I’ll send you one.

Second, Cayce made me start a new volume to her story and the first book is now finished, except for editing. Right now, it’s on my Patreon in full, but it will shortly be available on Amazon.

Third, it’s still possible to join my Patreon for $5/month and retain that price forever. Everyone who joins at $5/mo will be grandfathered in, and not see an increase in price, when the subscription increases to $9.50 on Sept. 1st. Not only do patrons get to read the stories before anyone else, they also get ebook versions before they’re released on Amazon for no extra cost. Patrons can also comment on each chapter, telling me what you think – I read and respond each comment and they help a lot.

To join, click here:

https://www.patreon.com/user/membership?u=32955303

Chariots and why it was easy for Alexander to beat them

In Book 4, Cayce’s army fights the Ketzillians, armed with imposing scythe-chariots. She uses Alexander T. Great’s method of dealing with them, which is to have the infantry open up, allow the chariots through, with maneuverable forces waiting behind to deal with them. I thought it’d be interesting to have a brief look at the history of chariots and how Alexander arrived at this tactic. At the end of this short essay, I’ve included some interesting links to YouTube videos on chariots (I’m not affiliated with any of these channels).

Horse-driven chariots proved decisive tools of battle in the late bronze age, around 2000BCE, but as technology and horse domestication advanced, they lost their edge. Horses were domesticated around 4000 BCE, though perhaps initially through management of wild herds more than pastoralism (people have been managing wild animals for at least 30 000 years). Over time, people began to use horses as beasts of burden. Too small to ride back then, they were great for pulling carts.

Modeled after these early carts, the first chariots were more akin to wagons, slow and clunky, and used by the elites to slowly move around the battlefield, as platforms from which to toss javelins, shoot arrows, and possibly direct soldiers. The technology quickly improved, though, to the much faster two-horse, two-wheeled chariots we’ve all seen in movies. One person to drive and one person to launch arrows and/or javelins.

Bronze age bows initially didn’t have very high draw strength, limiting their range to 70-100 meters. With poor draw strength and lacking steel arrowheads, they had low penetration power, constraining the effectiveness of archer regiments. And this is where chariots come in handy. They’re highly mobile, getting archers close to enemy troops, moving in and out of missile range, and they allow a much greater supply of arrows than a single person could carry alone (the first video depicts a chariot with 4 very large size quivers around the chariot).

The historian Jack Keegan writes, “Charioteers were the first great aggressors in human history.” They allowed people from the Eurasian steppes to invade Mesopotamia and parts of India. Because chariots were so successful, and a major force multiplier for hundreds of years, they were held in high esteem and symbols of power. They were used for entertainment (chariot racing), reproduced in art, and religion (many culture’s deities of the time ride chariots). Here’s a contemporary image of the Persian Goddess of Water:

Yet, technological progression undermined the dominance of chariots. Advances in archery and steel, continued selection for larger horses, and improved infantry training and tactics eventually rendered the chariot obsolete.

The development of the composite bows, developing from around 1600 BCE and on, were made by laminating horn, wood and sinew, which dramatically increased their draw strength and therefore range to 300-600 meters. Combined later with the invention of steel arrowheads, composite bows greatly improved penetration power. These advances increased the effectiveness of archer regiments, reducing the need for mobile platforms, and also turned chariots into vulnerable targets as severely wounding or killing only one horse, the driver or archer, removes chariots from the battle.

Meanwhile, horses were becoming larger because of human selection, eventually large enough for people to ride them. And this allowed cavalry regiments. Several hundred years later, horses were large enough for fully armored soldiers to ride them.

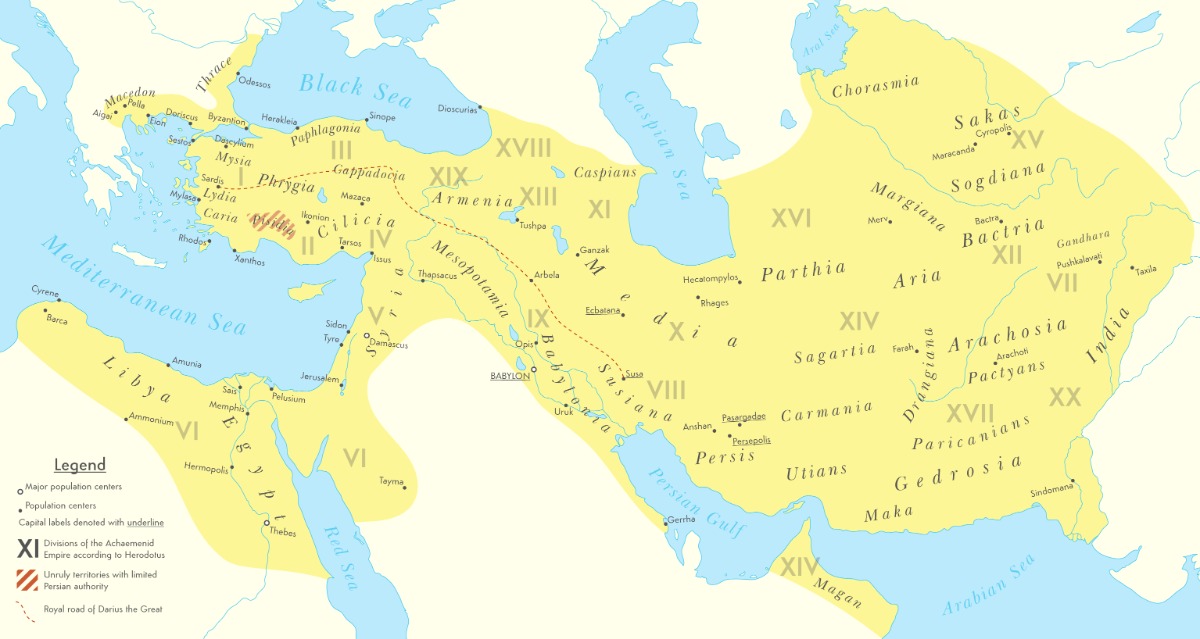

Cavalry are more versatile than chariots, have much greater maneuverability, can respond to changing battlefield conditions quickly, navigate uneven ground, and can be used as scouts. In fact it was cavalry that allowed the Achaemenid Empire (559–330 BCE) to create Persia, taking over what is now Iran, much of Greece, parts of Egypt, extending beyond Turkey all the way to India.

Persian Empire by Cattette - This image has been extracted from another file, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113179532

The last blow leading to the demise of light chariots was the development of structured infantry tactics. Early battles were largely unstructured, with individuals or groups of individuals simply fighting each other. As time went on, especially with the development of pike-infantry in Greece, improved training and tactics led to infantry capable of responding together as units rather than individuals. Where chariots could previously ride through individual soldiers around the battlefield, infantry formations constrained their movement, dramatically decreasing what chariots could accomplish.

Composite bows, steel, cavalry, and well-trained infantry, led to the demise of light chariot units. But chariots weren’t finished yet.

In fact, it was the rise of infantry formations that pushed the Persians to further develop chariots, turning them into a kind of tank and using them to break infantry lines. They were built heavier, more protected, and better armed. Wooden frames were expanded to allow up to three people (a driver and two archers/javelin throwers) and pulled by four horses. Serrated blades were placed on the axles of wheels, and at angles at the fronts of chariots. These were used to plough into infantry lines, their front scythes pushing infantry formations apart, while the wheeled spinning blades cutting through anyone in their way.

Again, infantry adapted. Phillip II created a professional army that drilled and drilled their maneuvers to become an unmatched military. Though he wanted to invade Persia, he died before achieving that goal and his army became Alexander’s. By the time Alexander invaded Persia, his army was well practiced in dealing with the fearsome scythe chariots.

Darius ruled Persia when Alexander invaded, and went out many, many times attempting to drive him off. Alexander won each battle, effectively chasing Darius around the empire, taking it for his own.

Their last battle is called the Battle of Gaugamela, and Darius likely had double the troops Alexander fielded (some 47 000 men), though historical records go all the way up to a million or so, which is likely exaggeration. Nevertheless, the Macedonians were outnumbered when Darius released his scythe chariots into the sarissa phalanx.

Heavy and fast moving, and poor at turning, Alexander simply had his phalanx lines open up, funneling the chariots into a kill zone where more maneuverable calvary and skirmishers waited. Darius was then able to slow the Macedonian cavalry with his greater numbers but realized he’d ultimately lose and fled the battle. Alexander’s army defeated what Darius left behind, and Darius’ own generals later killed him, pledged their loyalty to Alexander and thus ended the Persian Empire.

Though they dominated the battlefield for over a thousand years, shaping how civilizations across the globe advanced and grew, innovations in infantry, weaponry and horsemanship, moved chariots into obsolescence. At least in war. They continued on in entertainment. Rome hosted chariot races and included them in gladiator fights. And they remain cultural symbols, carrying the gods here and there.

YouTube videos about chariots and history (I’m not affiliated with any of these):

A short video (2 minutes) featuring a historian describing how they were used and then provide a demonstration:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dw_7nYDjHnw&ab_channel=SmithsonianChannel

A 20-minute-long video of how chariots became outdated:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBzHnd0Z7Z8&ab_channel=KingsandGenerals

Summer Specials – free books!

Clicking on the blue buttons below will take you to pages and pages of free books. If any of them interest you, enjoy!