Sunday Reads #85: Black Swans, Honesty, and Dishonest Statistics

Apr 05, 2020 4:16 pm

Hope you and yours are keeping safe.

I'm back again with the most thought-provoking articles I've read in the week. (in case you missed my previous newsletter, you can find it here).

This week, we first examine why COVID-19 took us by surprise, even though it shouldn't have. Why it was a Black Swan, even though so many people had predicted it.

In such tumultuous times, honesty in the workplace is paramount. Especially with lockdowns and what they imply for job security. That's what we talk about next.

Last, we look at how easy it is to lie with statistics. The epidemic is a case in point.

Here's the deal - Dive as deep as you want. Read my thoughts first. If you find them intriguing, read the main article. If you want to learn more, check out the related articles and books.

[I know this week seems heavy on COVID. Next week will be different].

1. Yes, COVID-19 is a Black Swan event. But not for the reason you think.

Many pundits call COVID-19 a Black Swan event. And I have done the same. In countless conversations with clients, suppliers and others, ruminating wisely, "yes, it's a black swan event. All bets are off."

But is it really?

Black swans are supposed to take us by complete and utter surprise. Unpredictable before the fact, inevitable after.

But, a lot of people have predicted this pandemic. Not only predicted it, but also highlighted how unprepared we are. Among the famous examples, here's Bill Gates, warning of a pandemic that could kill 33 million. And the resemblance of the current situation to the 2011 movie Contagion is eerie.

So, no - the epidemic was foretold.

What wasn't foretold though, was the immediate and devastating economic armageddon. That was the Black Swan.

In case the whole image doesn't show, scroll all the way to the right. That spike at the far right of the graph - from 300K jobless claims to 3.3 million? That was the Black Swan.

The video in this tweet illustrates this vividly. (I couldn't figure out how to embed the tweet in the email).

Experts (and movies) predicted, sometimes in frightening detail, how medical capacity would run out. How we'd wait, interminably, for a vaccine.

But they didn't think - what will happen if everyone has to sit at home for two months? What will happen if every business closes, all at once?

Like all Black Swans, seems blindingly obvious after the fact. Hindsight, especially in the case of Black Swans, is 20:20.

Alex Danco talks about this in his article on Black Swan Events.

Separately, the chart above also explains why so many democratic heads of state reacted slowly at the start.

In The Dictator's Handbook (an excellent book on Politics and Game Theory), Bruce Bueno de Mesquita says,

Politics is about getting and keeping political power, not about general welfare. Leaders do what they can do to come to power, and stay in power.

That's what happened.

In the early days of the pandemic, COVID-19 was an unknown quantity. Many hoped prayed fervently that it was "just another flu". On the other hand, every head of state knew what a lockdown meant. Unemployment.

And in any democracy, unemployment means one thing for sure - the leader in power crashes out in the next election.

Like Upton Sinclair said, "It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon him not understanding it."

2. The importance of honesty in leadership

If the labor statistics above are any portent of things to come, many of us, and many people we know, will lose our jobs in this crisis.

The luckier ones among us will have the hard task of telling others that they have to be let go.

When delivering such a rough message, it's useful to remember Ben Horowitz's article on the importance of honesty, "How to tell the truth".

- Don't hem and haw. This situation is worse for the recipient than it is for you.

- Don't say it's a performance issue, and deflect ownership.

- Don't wring your hands in helplessness. Accept that you, and the company, were ill-prepared for this scenario.

- Be authentic.

Level with your teams, with your employees. Yes, it makes you vulnerable. But they're far more vulnerable than you.

If you have to let them go, tell them straight. Tell them how you'll support them in finding their feet again (or if you cannot, tell them that honestly too).

If you will retain them, tell them that too. So they can stop worrying and focus their energies on helping the company survive.

3. How statistics lie. Or why COVID case counts are meaningless.

Statistics tell only half the story. Or in some cases, nothing at all.

Current reporting on the COVID crisis is a case in point. Inasmuch as: the number of COVID-19 cases is not a very useful indicator of anything.

Those numbers that we pore over every morning, that we hotly debate in our Whatsapp groups, that we are sure we've found a yet-unseen pattern in? Worthless. Or at least not worth much.

Why? Because the COVID pandemic is not a well-designed scientific experiment. When you're busy fighting a war, you don't stop to ensure that it's being recorded properly.

Hyperbole (or not) aside, the "design" of a study is a huge influence on what the data reports. Pertinent to COVID itself, as Nate Silver explains in his article, testing patterns have played a huge role in the number of cases reported.

Some ways in which the case counts paint an incorrect picture:

- If a country has limited testing capacity, tests will be reserved for the most sick - the 10% of afflicted who show up at the hospital. Grossly undercounting the actual spread of the epidemic, while leaders are busy congratulating themselves on flattening the curve.

- If a country is testing in huge numbers (e.g., Korea tested 1 in 170 of its population), then 'false positive' cases (i.e., those who don't have the virus but incorrectly get a positive result) would swamp the results. This WILL happen, even if the test returns false positives only 1% of the time. (in fact, this kind of phenomenon is the first example in any explanation of Bayesian reasoning)

- If the number of tests is suddenly increased, it can overestimate the growth of the virus. Germany, for example, is conducting about 50,000 tests per day — 7x more than the UK. So it has more than twice as many reported cases as the UK, but also only about one-third as many deaths.

- And of course, if a country ramps down its testing (either because it ran out of capacity, or for... ahem... PR reasons), then the situation could be getting actively worse as the case counts reduce and the citizens celebrate.

Nate Silver's article has a few detailed simulations (which you can download and play around with), explaining how simple assumptions about testing can cause wide deviations between reported numbers and actual cases.

Moral of the story?

Never trust just one measure. As Andy Grove says in his book, always pair multiple indicators, so that incentives stay aligned.

In the case of COVID itself: Don't look at number of cases alone. Also look at the number of tests done.

Always keep Goodhart's Law in mind - "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

4. To end on a more positive note...

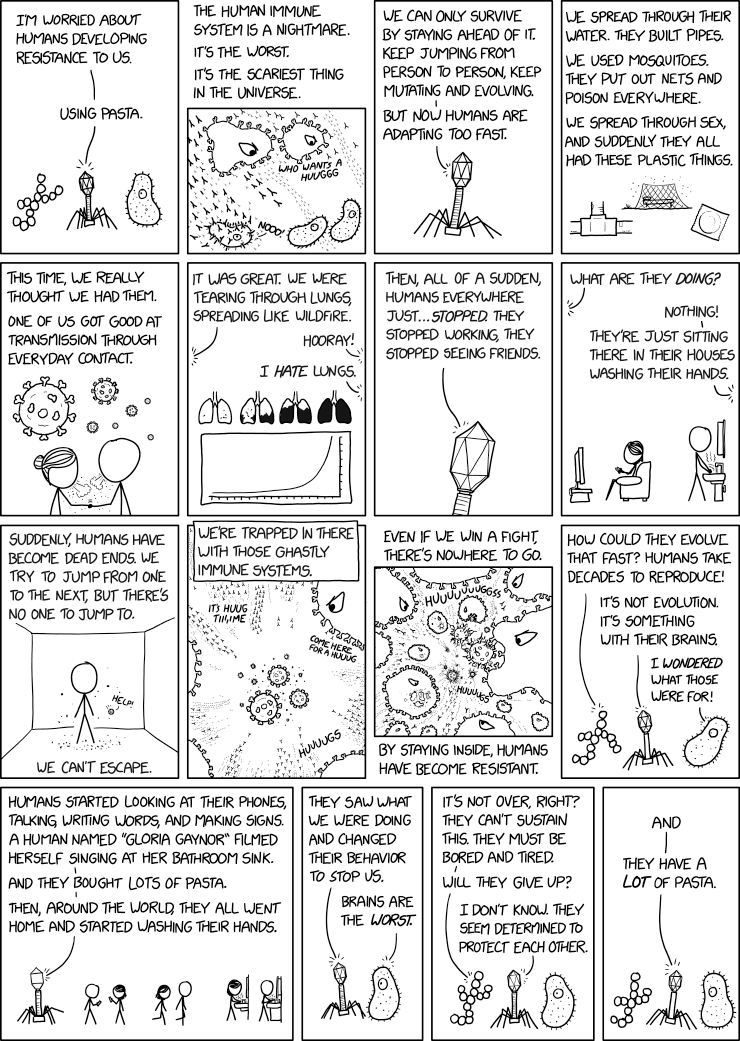

Here's a great xkcd comic about the current crisis.

As Randall Munroe (the author) says,

We're not trapped in here with the coronavirus. The coronavirus is trapped in here with us.

That's it for this week! Hope you liked the articles. Drop me a line (just hit reply or click on the "Leave a comment" button) and let me know what you think.

PS. If you like the stuff I send you every week, I'd be honored if you could forward this to a friend so they can subscribe. Thanks a lot!

Jitha