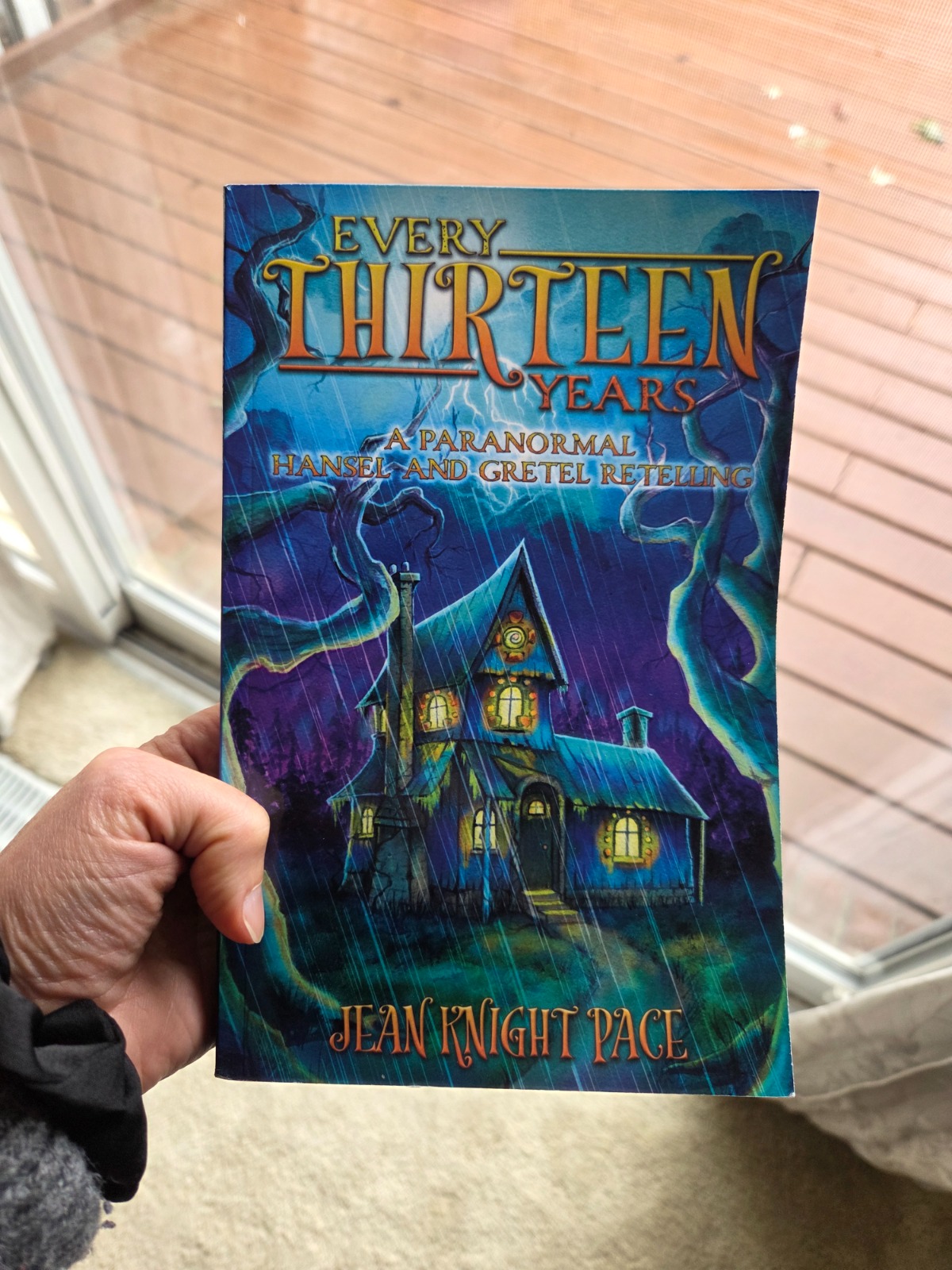

Every Thirteen Years... Is HERE! Plus, first chapter.

Oct 28, 2025 1:51 pm

Every Thirteen Years has arrived! It's gorgeous. Reviews are starting to roll in and if you've left one, I appreciate that so much! Here is one from Phoenix Fyreheart (thank youuuuuu!!!) on Goodreads:

Every thirteen years in the month of May, a child disappears in the woods.

It's been thirteen years since the last disappearance and all the parents in town are warning their children: stay out of the woods. But when there's a party to go to and mom says no, you do what any teenager would do. You go.

Hans is a typical teenage boy with zero bothers to give. Greta is his little sister who desperately wants him to love her as much as she's always loved him. So when he slips out of the house for a party to celebrate the end of May, she tags along. Things get weird really fast though, and all paths lead back to the same cursed cabin. Can they figure out the mystery and escape its clutches together, or will they lose each other to the magic?

Every Thirteen Years is a paranormal retelling of the infamous story Hansel and Gretel. It's both familiar and strange all at once. Just when I thought I had figured it out, an unexpected twist had me questioning myself. And then another twist left me scratching my head until the final reveal I never saw coming. The author did a great job at keeping me guessing, the answers just barely out of reach like a carrot on a string. This made the ending ridiculously satisfying to read and left me feeling complete, in a way. It was engaging even though the story blooms from familiar roots. Similar, but different enough to be interesting. I give this tale five stars!

If you're wondering, do I really want to read this book? Well, of course you do! Here's the first chapter to convince you...

Greta

The one good thing about Daddy leaving was that the screaming ended.

That’s not the way Hans remembered it, but I did.

I’d hated that yelling—day in and day out. Daddy and Mama, their voices fit to shatter walls.

We remembered a lot of things differently—Hans and I. And when we did, Hans always said it was because I was practically a baby when Daddy left.

Not true.

He just said that when he wanted to be right about Daddy, which was a lot.

And why was I thinking about Daddy anyway, when I had chores to do?

I scooped up the broom. One thing about chores—the doing made me feel better than not doing. Especially this afternoon.

Hans had stormed off again—probably to play a video game at his friend’s house. Mama said that’s how teenagers did things—all stomps and grunts—but I didn’t like it.

I liked the sounds that came from soft mosses and leaves caught in the wind. From paths made of dirt and decay that would barely make a sound no matter how many times you tromped on them.

I moved our dirty shoes out of the way so I could sweep the crusted mud they always left by the door. Then lifted my backpack off the floor, cleaning under it.

Soon as that was done, I moved on to the dishes, counters, the table in the nook where Mama liked to eat breakfast and watch the birds.

When Daddy left, things had fallen quiet. Not soft moss quiet either. Not at all. It had been a sharp silence—the type you heard at every turn, with every step, under every whisper. That silence hadn’t broken until we’d moved to Grammy’s old house—a maze of rooms encased in dusty wallpaper held in place by bowed ceilings and crooked floorboards.

The house wasn’t much—that’s how Mama had put it—but it was ours.

I thought it was perfectly much—big old rooms with nooks and crannies, places to play, places to hide, places to sit and read a book. Places where our laughter could finally wake up, as though we were shaking it out after a long winter.

Much better than the house we’d lived in with Daddy, which had been a tight combination of square angles and open floor plans.

This house had spaces. Inside and out. Because this house also had woods—right behind us, miles and miles of green and bark and berry. Not that we were allowed miles and miles out. Mama made that very clear with the bright orange markers she set all around our property.

Of all that deep vast wood, we owned only five acres. Though back when Hans and I had roamed together, we had often slipped through those barriers to explore the bigger woods beyond. These days, though, I stayed inside the posts.

I picked up my backpack, sorting my books—one about birds, one about flowers, one about a little girl with no parents who lived in the woods in her own little cottage.

I always imagined those woods parting for me, just like they did for the girl in my story—branches and bramble moving aside as I walked along loamy paths. And in a way, maybe they did.

I almost tucked the backpack into its nook, and then thought better of it. My chores were done, the house empty, the late sun calling me to it. I slipped the backpack onto my shoulders, slipped my feet into my shoes, slipped a granola bar into my pocket, slipped my way out the back door.

All in a steady silence that only the woods could appreciate.

They made room for me, the woods. Like they made room for everything that was willing to muscle its way in. An insistent vine wrapping around a tree, a little sprout popping out of a cluster of rock. The woods were busy, bossy too. Like some sort of too-full Thanksgiving gathering. Everyone who wanted to come was invited, plopping down wherever they could make a place for themselves.

Just what I needed after Daddy left.

Just what I needed when the house got too empty.

Just what I needed today.

Space.

But not space away, space deep in.

I hiked farther into the woods, to my favorite place where the sunlight went green because the trees grew so thick, to the place just before Mama’s orange posts that marked the edge of our property.

Hans had liked the woods at the beginning too. When we’d first moved here, he’d explored them with me—way past Mama’s posts and the old barbed wire that set off the other property. The vast woods had been ours then. We’d made up games, carved in trees, played hide and seek.

And then he’d grown up. Well, sort of.

And I didn’t like it.

Teenage Hans reached back toward the normal, the neat, the plain—toward the taut corners of our old life.

Which brought the yelling back.

Only now it was Hans and Mama. I hated the yelling even more with them. I was terrified that, just like with Daddy, Hans would walk out the door and never come back.

I couldn’t bear to lose Hans.

I couldn’t bear for Mama to cry again like she had with Daddy.

And I couldn’t bear to be the only one left.

I sank to the ground, right next to my favorite tree—one Hans and I had carved our initials into when we were young, well, younger. I had a little stash of stuff there, like I was a squirrel or crow. Smooth stones, snail shells of different sizes, various feathers and interesting leaves. Like a fairy garden. Only I didn’t need a fairy to come to it. I just needed a place to come to myself. Did that make me the fairy? Probably not with my short legs, all scraped up at the knees, and hair that wouldn’t stay braided, plus a face that was starting to thin, but not in a beautiful way like Mama’s.

When Mama and Hans yelled, and then when they finished and sprang apart like two same-sided poles of a magnet, I never said anything, never talked about it at all. But I used that quiet to organize Mama’s pens and pencils and chalks. Or do the dishes. Or, if I was feeling extra still, I’d sometimes even do Hans’ chores, cleaning the toilet and dusting the furniture. He never seemed to notice, though I know Mama did.

And on days like today, when it had gotten really bad and both of them had burst apart to their own separate corners of their own separate worlds, I retreated to the silent calm of the woods. Wandering. Orange post to orange post.

I knew every inch of our property, while not knowing it at all. That was the beauty of the woods—every day a different sky, every plant a changing thing, every step on different dirt than the day before. I loved that.

Today a whole cluster of mushrooms had burst out of the loam, right behind our tree. Blue-tinted tops, creamy bellies.

I plucked one and wrapped it in a tissue.

Because sometimes, after the screaming was done and the tautness of the house started to unfurl like a fern in the morning, Hans would come home and I’d show him a caterpillar or bone or something else I’d found in the woods. Usually, he’d grunt and mostly ignore them, but sometimes he’d look them up on his phone and tell me which caterpillars would turn to butterflies and which were destined to become ugly brown moths. Or whether it was the bone of a bird or snake. Things I already knew before he looked them up, but I let him tell me about them anyway.

I figured with this mushroom, he could tell me if it was a type we could eat or if it was one that would kill us dead in minutes. And to be honest, this time I had no idea.

Usually after he looked something up, he started to feel better. And maybe after that we’d play a game of Scrabble. Just like we used to, before he was a teenager, and before I was whatever this awkward version of the old me was.

Because I was growing up too.

Mama was starting to talk puberty. She didn’t need to. At age twelve, I could feel it coming for me—claws out—the moodiness, the acne, the uncomfortable conversations. When I much preferred soft silences.

Which is why, as opposed to Hans who never went into the woods anymore, I spent more and more time there.

Until one day I didn’t.

Facebook Group Jean Knight Pace Writes